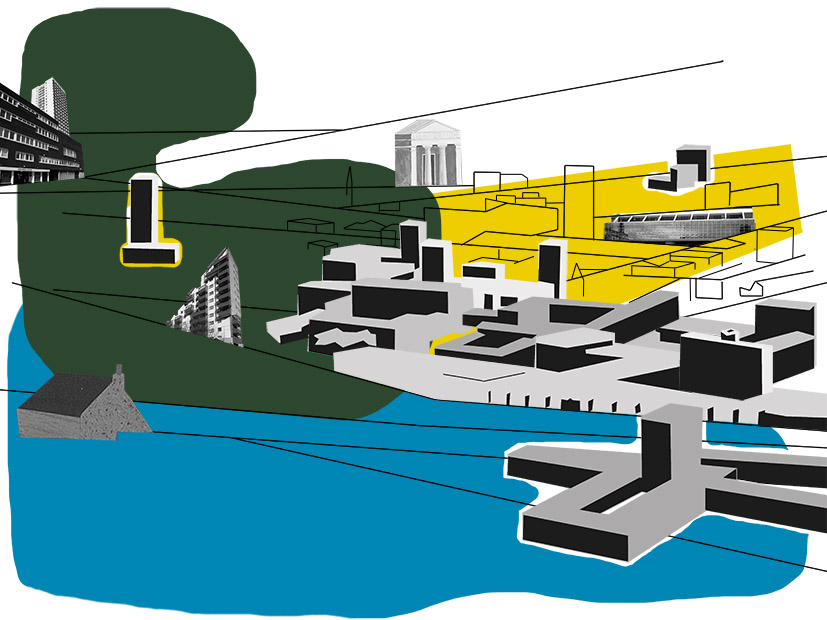

As part of Overmorrow, the NewBridge Project is commissioning a permanent monument to the present. Rather than memorialising an individual, we want to commission a monument that memorialises society here and now by enabling people to encounter each other – a bench, forum, platform, playground. It will serve as a piece of infrastructure that is a direct invitation to stay and enjoy, a welcome without hostility.

The monument will be designed to be interacted with and activated by the public, and will be installed in an outdoor environment. The monument will also be movable inorder to be enjoyed by different communities and activate new environments. Its’ ambition is to reflect the values of Overmorrow – one that imagines a better, more equitable and more open present; that promotes solidarity, mutual support and nurturing social relationships – to disrupt the idea of what a monument can be.

The recent toppling of the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol, following 2020’s Black Lives Matter demonstrations in the wake of the killing of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis police and countless others, has given greater visibility to the debate around public monuments.

This debate is not new, and is too often focused on the individuals memorialised, failing to address the more important questions of why we build monuments, who and what we choose to memorialise, and what our changing attitudes and attachments to these monuments reveal about our own values as a society.

Both in the UK and across the world, monuments are built to those who have accrued great wealth or power, or as a demonstration of the might and reach of the state. Installed in our public spaces, they often become symbols of nationalism and fail to reflect the society they stand to.

Public spaces should be antidotes to frenzied cities and bleak, urban sprawl. But neoliberalism and globalism have undermined their civic roles, transforming public spaces into products of spectacle and private interests. For years we have tussled with ideas around ownership of privately-managed public spaces, and the deployment of “hostile architecture” designed to stop people loitering and lingering.

These designs often attack the most vulnerable people in our communities, sending a very clear signal that certain people aren’t wanted. Now more than ever we are seeing individuals and communities across the globe being forced to isolate and separate. Lockdowns have emptied our public spaces or made them unavailable, with benches and resting places in particular being covered in hazard tape or entirely removed. The pandemic has again raised questions around the use of public spaces, and how they are an integral part of our networked cities whether for recreation, movement, habitat or a sense of place.

How do we unlock spaces for their true public value?

‘Some years ago I was talking to Le Corbusier about Peter Yates

with whose work he was familiar, this boy can see

things said he,

but to me it seemed more relevant that Peter could do

things.

In his paintings he prodded the depths rather than depicting the

surface.

Simmering passions behind the stony immobility. Cathedrals like rocks and rocks like cathedrals. From

the vision of

his beloved Durham locked in the mist of time to the

Ultramarine

rhapsody of Cyclopic islands.

By staking claims on the distance he excites the

imagination.

Simplicity, directness and purity give his work the

power .

That was Peter Yates my friend the poet architect.

The song is over but the chords go on vibrating’.